In 2019 I decided I was ready to pitch my first novel, Schopenhauer in Love, to literary agents for the first time. I taught myself how to write a query letter, researched agents for those most likely to have an interest in a work of historical fiction about a 19th century German philosopher[1], read the best novels these agents had brought to light, wrote personalized letters only to those most likely to get excited by a book like mine, and tracked the letters I issued in an Excel spreadsheet.

I wrote to seven top-flight agents, managing to convince three of them to read the manuscript. Nicole Aragi, the rock-star agent of rock star authors Junot Diaz, Rebecca Makkai, and Colson Whitehead, was among them. Three out of seven was an extraordinary result.

But the rejections suggested I was a better writer of query letters than author of a novel. I needed a makeover, to shake things up. I needed either to become a better writer, a more interesting person, or both.

I concentrated on reading mostly women authors, authors of color, or authors outside of the United States. I tried writing poetry. I joined George Saunders online short-story course “Story Club”, drove around the country in a campervan, took up French, and read books on the theory of the novel and fiction writing. I purchased an Internet domain name, biketoenddivision.org, and chronicled an attempt to ride a bike around Lake Michigan, raising money for West Town Bikes, a bike shop dedicated to supporting youth on the West Side of Chicago.

I fooled around with the idea of teaching after a few of my friends encouraged me to try. I had started putting more time and energy into helping other writers improve. My mother had been a teacher. My brother taught. I have many friends who are teachers. I felt like there was something to it that resonated with me innately.

At my mother’s memorial last June, one of her friends remembered a motto that epitomized my mother’s moral foundation. It was:

To lift yourself up, lift up those around you.

Though mom ‘s sturdy example ingrained the principal of this motto deep within me, this artful expression of it made it brand new. I already knew the value of the idea. With mom gone, I was that much more eager to put it to use. Soon after a non-profit group that helps kids in the city discover their ability as writers put out a call for volunteers willing to work in their booth at Chicago’s 2022 Printer’s Row Literary Festival. I had taken their training a year earlier, passed a background test, and had been waiting for an assignment ever since. I wanted to establish myself with the org and parlay it into a gig teaching writing and running one of their workshops.

Another great Carolyn motto is:

Whenever somebody asks you to do something, always say yes. You never know where it will take you.

This idea too had worked its way into my being.

I signed up. It was a beautiful day in late spring in downtown Chicago. The festival had its own buzz and energy. It was great to be in the throes of so many books, book lovers, and authors. I bumped into a cherished novelist friend, hawking copies of her first publishing success, The Fourteenth of September, as I had hoped.

I had a brief few moments to learn the pitch for the program, what they expected out of me on that day, and to acquaint myself with my peers who had also committed to the first shift on opening day.

I was soon standing side-by-side with another more experienced person, either a volunteer or a staffer, getting people to sign up for our mailing list or to purchase a book of student poetry and art. As an unpublished author, it was easy to imagine and describe the thrill that young kids would get from reading their own words from the pages of a published book in front of a live audience.

The booth work energized me. I was chatting it up with everybody, the people who approached the booth and the persons I worked with. It seemed like my partner and I were racking up good numbers in book sales and signups. We high fived each other a couple of times. I put my arm around her to get our picture taken together. By the end of our stint, I was happy and satisfied for what we had accomplished.

I felt like I had inched closer to my goal of teaching.

At Goldy’s bar in Forest Park, having a beer with my brother, I failed to choke down a goofy impulse to blurt out how he must be glad that our mother had died. I regretted it immediately not because it was crass but because it reinforced an old script of how he was put upon by his mother.

We were in our cups. I doubled down on my stupidity, warning him “don’t be a victim, bro”, giving him an unsolicited lecture on why he shouldn’t go on blaming mom forever. The evening ended badly. I went home fearing permanently ruptured my relationship with my only brother.

Soon after, the volunteer coordinator sent out a group email looking to recruit a crew to assist in running the annual fall fundraiser charity event. I again want to help, check coats, distribute paddles for the paddle raise, do whatever was called for. I wrote to tell them that I was interested and ready to go.

When I didn’t hear back, I wrote a second email. The coordinator responded saying something vague about background checks which surprised me. They had the results of my original check on file. I found the results on my computer and posted a fresh copy of them to the coordinator. She wrote back to explain that they had already met their quota for volunteers.

Maybe they didn’t need me. Although it was starting to smell fishy, I bought two tickets to the event and proudly invited a new friend to join me, not suspecting there was anything really wrong and wanting at least to support them as a donor and have a fresh chance of getting to meet some of the staff and chat with fellow boosters.

Then, on a Friday, I got an email from the executive director disinviting me from the charity event. He explained that he was rescinding my tickets, having received a report from staff and volunteers of “significant inappropriate behavior”.

It was a rude shock. As accusations go, or quasi-accusations, I had never experienced anything so damning. I was confused, embarrassed, and humiliated. I wondered what people would think I had done to warrant such an extravagant reaction. I couldn’t even explain it to myself. I jumped on the director’s offer to reserve half an hour on his electronic calendar for a one-on-one discussion. I picked a time for the coming Monday.

Over the long weekend, I called friends and family on the phone, confessed my circumstance, and appealed to them for moral support. I called my new friend and suffered the compound embarrassment of having to give her the whole background to the story as a prelude to the explanation of why I had to disinvite her.

The last person I called was my brother. Likely I was more hesitant to tell him my story. He was sympathetic, thoughtful and supporting. He heard me out. But before the call was over, he found a moment to admonish me without a smirk “don’t be a victim, bro.”

Now here was change of the most exquisite kind. The kid brother schooling his know-it-all elder on the finer points of life. The kid brother outsmarting him with a dare to sample his own medicine. The kid brother showing the older brother how to listen.

I woke the next morning, still thinking about that comeback, laughing my head off at this unexpected reversal. Who was doling out advice now? If this was a game of chess, my brother had just taken my queen.

The next day the director confirmed that putting my arm around my booth partner was the crux of the complaint against me. I offered to write a note of apology to that person and entrust it to the director for delivery.

I also offered to write another note to the rest of the volunteers and staff in case some aspect of my behavior had caused them to suffer in some way as well.

We spoke of a future day, in a following month, when we might deem it appropriate to reevaluate my volunteer status.

I wrote a formal apology, addressed to my erstwhile booth partner in an email, asking for her forgiveness for my affront. I did my best to put myself in her shoes. I sent the result to the director the next day and felt good about it.

A few days after that, in a final spasm of agony, I wrote a brief follow-up email to the director thanking him for hearing me out and telling him I felt demoralized and we could drop the idea of reevaluating my volunteer status.

I did not hear from him after that.

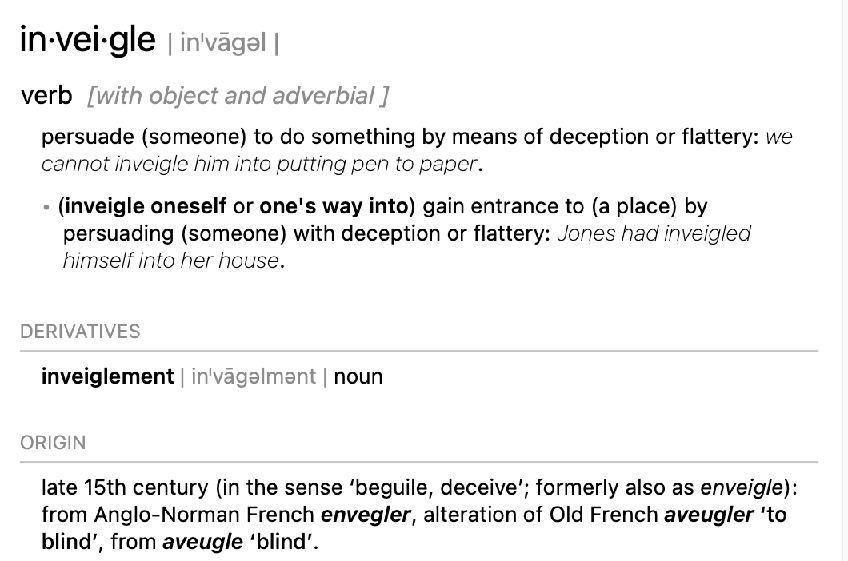

The only other complaint leveled against me was an accusation of oversharing. People who know me would readily believe this charge. I don’t deny that I am in the eyes of many an over-sharer. Hell, a lot of people I know are under-sharers and I don’t hold that against them. I just don’t feel oversharing should be a source of shame. If somebody accuses me of oversharing and what they’re really doing is euphemistically telling me, I’m a bore… fine. Go ahead and shoot me. But if not, then it might mean that all I’ve really done is lead a longer and more interesting life than most folks.

Coda

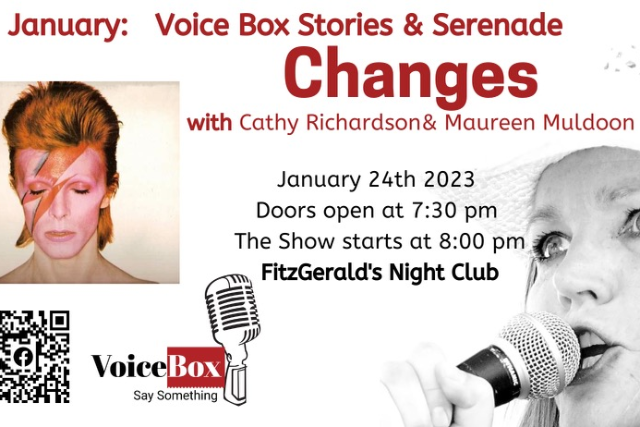

This story was developed and presented at the first Voice Box performance of 2023 at Fitzgerald’s Nightclub in Berwyn, II. Our theme for the evening was “changes”, as inspired by the David Bowie song.

A special thanks to Maureen Muldoon and Cathy Richardson for encouragement and a riotous, fun setting for “getting real”.

-

They exist. ↑