Now in 2024, a nail-biting U.S. Presidential election year, what does Dante Alighieri have to tell us about today’s 4.83 million13% of today’s 161 million registered voters undecided voters?

After the Oct 1st vice-presidential debate, an ABC news journalist, huddling with a tiny sample of the evening’s 39 million2Rick Porter, “TV Ratings: VP Debate Falls 25 Percent vs. 2020,” The Hollywood Reporter (blog), October 2, 2024, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/tv/tv-news/vance-walz-vp-debate-tv-ratings-1236022692/. viewers, kept circling back to one wishy-washy “undecided”, hoping against hope that on a successive round this person would suddenly form an opinion.

“How,” I wondered, “could anyone be that insipid? More maddening still is that these undecideds have amassed clout that is grossly out of proportion to their numbers, as if it is their apathy that makes them powerful. And what if we, the audience, were equally pathetic for lavishing the undecideds with so much attention?”

As I struggled to find voice to the nausea which this spectacle inspired in me, I remembered the 13th century Italian poet, Dante Alighieri, and his concept of the “neutrals”:

…melancholy souls of those

Who lived without infamy or praise.Commingled are they with that caitiff choir

Of Angels, who have not rebellious been,

Nor faithful were to God, but were for self.

The neutrals are either angels who cannot choose between God and the devil or plain folk who make so little impact on the world that they inspire neither infamy nor praise. They are cowards. They are selfish. They make no mark on history.

It was Dante who seized upon the genre of the epic poem, in particular Virgil’s Aeneid, and mutated it into a Christian allegory. Whereas the Aeneid ties the foundation of Rome to its hero, the Trojan warrior, Aeneas, the Divine Comedy makes a hero out of an everyday pilgrim, a commoner, on a fearsome quest to seek salvation. Dante audaciously elevates the courage it takes to find one’s path to eternal glory to the same height as the courage it takes to found a nation.

By reimagining the epic, Dante shows that any person, who embarks on a quest to achieve redemption—however noiselessly, however bereft of fanfare—is a hero.

Except for the neutrals. What about them?

But because thou art lukewarm and neither cold nor hot, I will begin to vomit thee out of my mouth. ~ The Book of Revelation 3:16

These words from the Book of Revelation prefigure the extraordinary contempt Dante held for people who refused to take sides, sat on the fence, or found other ways to be wishy-washy, apathetic, uncommitted, or unconcerned, couch potatoes before the invention of television.

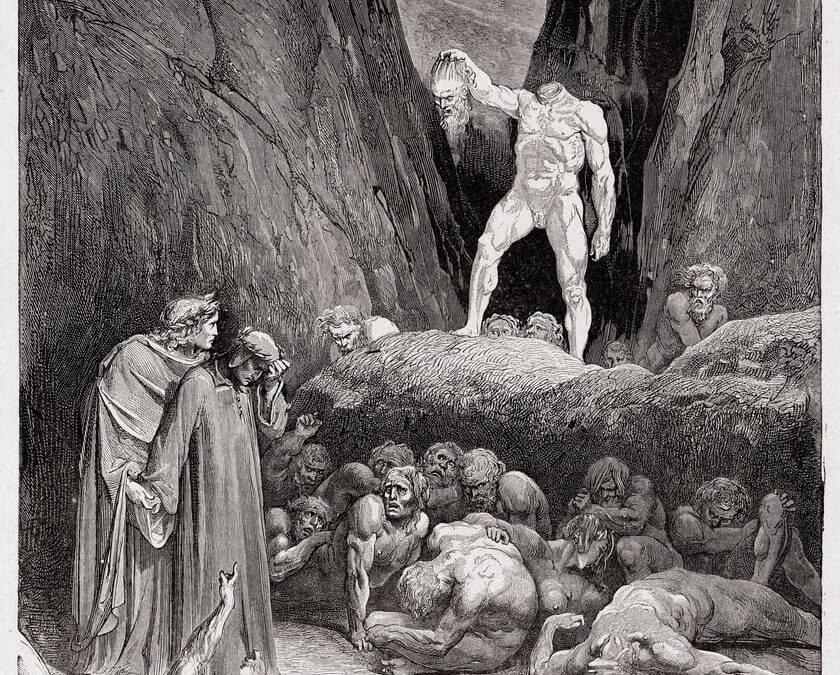

Dante scorns the neutrals so completely that he doesn’t grant them a place anywhere in his masterpiece. Their place is fittingly a non-place. The putative “vestibule”3Barolini, Teodolinda. “Crossing and Commitments.” In Commento Baroliniano, Digital Dante. New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries, 2018. https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/dante/divine-comedy/inferno/inferno-3/. In her commentary, Professor Barolini’s observes that “This space, the ground of transition, is not named by Dante; in the commentary tradition it is frequently called Ante-Hell or vestibule.” This is just one of a number of insights Professor Teodolinda provides in her comments on Canto 3. where we find the neutrals is an anteroom just outside the entrance to hell. They are such utter non-entities that Dante refuses to give them names, or a location in time or space. More than refuse, more than contempt and disgust, poetic logic defies him to recognize them at all4No way was Dante going to permit the neutrals to mar the symmetry of his masterwork, which he divides into the proportional realms of hell (the Inferno), purgatory, and heaven (Paradiso), each consisting of thirty-three cantos, a very particular number in deference to Jesus Christ, the savior’s, time on earth..

Dante banishes the neutrals from his masterpiece to mirror how Dante himself, the real-life Dante, was exiled from his beloved city-state of Florence. The causes for exile between Dante and the neutrals could not be more distinct. The neutrals, those who steadfastly refused to enter the fray, perfectly oppose the temperament of Dante, who engaged in Florentine politics with a knife between his teeth. How did Dante get banished from his hometown? For a cause, astonishingly relevant today. Long before our nation was formed and its constitution written, Dante, it turns out, fought for the separation of church and state!

At first, it is bizarre and difficult to absorb logically how Dante despised apathetic people more than the persons in hell, a holding tank for murderers, rapists, frauds, and traitors, which today would include the prison guards at Auschwitz and, from the most recent headlines, the Frenchman who night-after-night drugged his wife and invited other men to rape her in her own home while she was helplessly unconscious5“French Village of Mazan Torn Apart by Horror of Mass Rape Trial.” Accessed September 16, 2024. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cyvpd7zyprdo.

.

Dante puts the neutrals just outside the entrance to the Inferno, at the very beginning of the Divine Comedy itself, at the opposite extreme from Paradiso where Beatrice makes a pronouncement on the majesty of free will:

“The greatest gift that God in His bounty made in creation, and the most attuned to His own goodness, and that which He esteems the most, was the freedom of the will.”

Paradiso, Canto V, lines 19–22,

The neutrals by “doing nothing” most obscenely scorn God’s greatest gift to mankind. By spiting God’s supreme gift, free will, they spite God Himself and all of His creation.

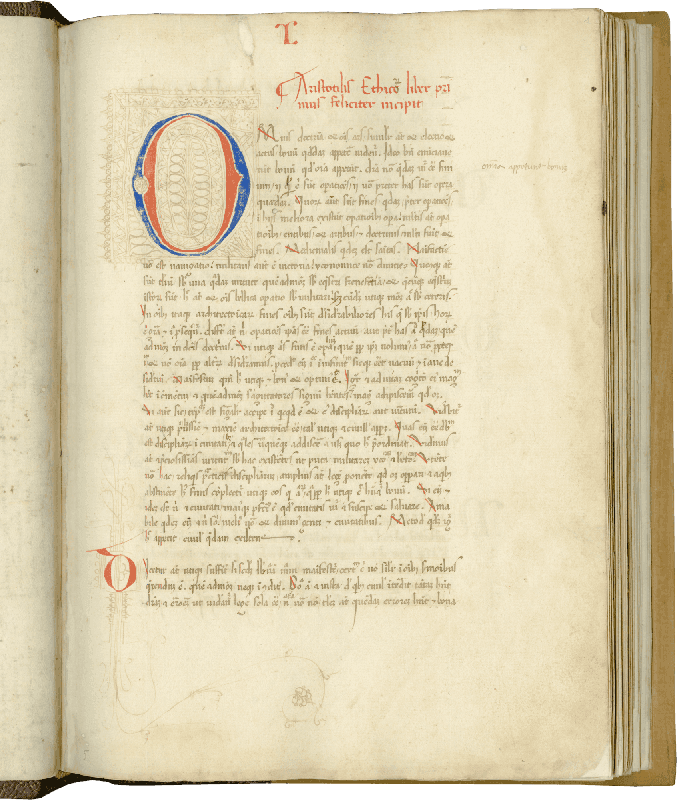

In the introduction to his political treatise, On Monarchy, Dante gives the motivation for writing it as “lest I should someday be found guilty of the charge of the buried talent”, an unmistakable allusion to The Parable of the Talents. In that tale, a master entrusts a single talent to his least resourceful, let us say, oafish, servant, who fearfully buries it in the ground. In so doing, the servant forfeits his chance to preserve his master’s trust. The master, infuriated upon learning that the servant has squandered the talent entrusted to him, gives the servant a humiliating tongue-lashing. The master’s furor is greater knowing that his other servants made wise investments which earned him handsome rewards. The master takes the talent back from the servant in disgust.

For Dante, the parable itself is a gift6This is an uncanny feature of the parable. Once you recognize the parable itself as a gift, watch out! he dares not ignore. In his genius, the poet takes this figurative threat literally. And so, in the introduction to his treatise, he makes it loud and clear—in case God is watching—that he is heaven-bent on heeding its intent.

Dante also makes it clear that God has given him and him alone the supreme qualities required to write On Monarchy. It is a delicious fusion of humility and supreme confidence.

This is why Virgil in Canto 3 explains to Dante, the pilgrim, that the neutrals forego “the good of the intellect”. The supreme cost for not exercising their God-given free will, not using their minds, is to lose them.

By abjuring the privilege to take a stand, the neutrals don’t make an initial decision. Stymied from the first decision, they’ll never make farther decisions, those which would naturally follow from the first. The whole process of being human is cut-off before it gets started.

By 1247, a medieval scholastic, Robert Grosseteste, had translated Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics from Greek into Latin7Jean Dunbabin, “ROBERT GROSSETESTE AS TRANSLATOR, TRANSMITTER, AND COMMENTATOR: THE ‘NICOMACHEAN ETHICS,’” Traditio 28 (1972): 460–72.. By the time Dante was born in 1265, the Peripatetic doctrine of “habitus” was already familiar to Dante’s influences, particularly St. Thomas Aquinas.

Habitus derives from the translation of hexis (ἕξις), “state” or “disposition” as found in Aristotle’s Ethics. Habitus is a stable condition of the soul that is achieved through deliberate and purposeful action. It is only obliquely related to the modern meaning of habit. Rather it can be said that a constant regimen of good habits leads to a good habitus. A person trains her soul just as athletes train their bodies. In this way, repeated acts of charities slowly, methodically develop a charitable disposition or “habitus”. Habitus is “secondary nature”. Habitus is the result of protracted willful purpose.

Eric Auerbach, 20th century German philologist and author of Dante, Poet of the Secular World, provides this definition of habitus:

It is the residuum in man’s soul of his soul’s history8Erich Auerbach, Dante, Poet of the Secular World (New York: New York Review Books, 2007)..

Persons are not born with habitus but accrue it over a lifetime. Until then we are ill-formed and unfulfilled.

In his book, Auerbach, shows the vital significance of the doctrine of habitus in the Divine Comedy. Dante’s sketches of persons inhabiting the inferno are crisp, tangible, and singular because they represent the final form of a person’s habitus, a lifelong accretion of willful acts that ultimately and precisely define the person.

He speaks of Dante’s “power to portray a man in the attitude and gesture which most fully sum up and most clearly manifest the totality of his habitus.”

Habitus justifies and explains the effectiveness of Dante’s go-to device in the Inferno, the counter-punishment (“contrapasso”), which matches in form the sinner’s transgression. By the time a transgressor reaches hell, his/her habitus has attained its perfect definition so that the transgressor’s contrapasso, his fate, is all but predetermined. All Dante has to do is draw a picture for the reader. It’s like matching a paint chip at the hardware store.

In the case of Dante’s contemporary, Bertran de Born, who was accused of creating a schism between a son, a prince, and his father, the king, i.e. heads of state, Dante finds the baron holding his severed head by its hair, swinging from his hand like a nightwatchman’s lantern, his decapitation, a gruesome if not apt example of poetic justice.

In Canto 28 of the Inferno, Bertran de Born recognizes the aptness of his punishment, “the law of counter-penalty”:

The doctrine of habitus greatly refines the notion of good and evil. It makes it possible to understand how a good person can do a bad thing and vice versa. If you have a corrupt habitus and do a good deed, that is an accident. Habitus is the imprint that develops from willful actions over time. While it is mutable, it is also extremely stable. It is like character (ἔθος) with less starch.

Habitus thus is extremely useful for a moralizing poet like Dante. Anybody who leads a purposeful, deliberate life can be a hero. And those who do will bear its imprint in their habitus.

But what does this have to do with our neutrals? We have seen that the neutrals are locked out of Dante’s moral universe. Not by Dante but simply by not being. It is ever so slightly worse than dying in obscurity. They are the undead on a technicality. Never having lived, they cannot die. Never dying, they get no tombstone. They cannot be remembered.

In Canto 3, Dante describes an infinite train of neutrals futilely chasing a wordless banner in hell’s antechamber:

And I, looking more closely, saw a banner

that, as it wheeled about, raced on—so quick

that any respite seemed unsuited to it.Behind that banner trailed so long a file

of people—I should never have believed

that death could have unmade so many souls.

Not only are the neutral’s obscure, but so is their number. But Dante leads us to believe that the number of neutrals encompasses the bulk of humanity. It eerily hearkens to the Parable of the Wedding Banquet9“Bible Gateway Passage: Matthew 22 – New International Version,” Bible Gateway, accessed October 5, 2024, https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Matthew%2022&version=NIV. where the persons invited to the king’s wedding respond with staggering indifference even after multiple invitations. Those that do show up are inappropriately attired and unprepared. This is the parable that ends with the ominous conclusion that “many are called and few are chosen”.

The parable critiques those who abuse their free-will with a sloth-like intellect prone to poor or pointless decisions.

Finally, we begin to appreciate Dante’s contempt for the neutrals and by proxy undecided voters. It starts to make sense. It is no longer outré. Neutrals are not even “good” enough to get into hell. The parallels of the neutral to today’s undecideds is also sufficiently clear that we see how Dante’s contempt transfers to them.

But let’s not get too smug. Dante begs caution. If the neutrals are vastly in the majority of humankind, how do we know we don’t number among them? Probabilistically, the odds are too great.

Among us, neutrals are not just undecided voters. Most of us are neutrals despite how much we’d like to think otherwise. We follow wordless banners, e.g. party slogans and the cant of political parties, latching onto the thoughts of others not our own. Without a habitus to guide our instincts, we behave like sheep or cattle, as members of a herd. If you asked us why we’re following a blank banner, at best we can parrot back a slogan. We value positions over fellowship. We mistake rage for passion, causes for a desire to dominate and control, fall victim to vanity with public displays of “righteousness”.

If we are neutrals, there is little chance that we would know it or admit it to ourselves. Ironically, we pride ourselves on our individuality. Who writes eulogies for milquetoasts?

Dante provides clues to this predicament. The path through the dark forest (selva oscura) is unknown and hence only discovered step by step in frightening solitude. It is not visible on a map or GPS system. It is unadvertised. It zigs and it zags. It brings on trials of characters. It defies avoidant behavior. As Joseph Campbell once said, “If the path before you is clear, you’re probably on someone else’s.”

Are we born neutrals or do we become neutrals? Do we—to borrow from an old joke10https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/103-be-not-afraid-of-greatness-some-are-born-great-some—have neutrality thrust upon us?

We’ll get into that in Part II. Stay tuned. In the meantime, I point you to Pope Francis’s apostolic letter, Splendour of Light Eternal11“Lettera Apostolica Candor Lucis Aeternae Del Santo Padre Francesco Nel VII Centenario Della Morte Di Dante Alighieri.” Accessed October 11, 2024. https://press.vatican.va/content/salastampa/it/bollettino/pubblico/2021/03/25/0181/00393.html#ing., written on the 7th centenary of Dante’s death, in which he beautifully argues for the enduring significance of Dante to a spiritual life.

Footnotes

- 13% of today’s 161 million registered voters

- 2Rick Porter, “TV Ratings: VP Debate Falls 25 Percent vs. 2020,” The Hollywood Reporter (blog), October 2, 2024, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/tv/tv-news/vance-walz-vp-debate-tv-ratings-1236022692/.

- 3Barolini, Teodolinda. “Crossing and Commitments.” In Commento Baroliniano, Digital Dante. New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries, 2018. https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/dante/divine-comedy/inferno/inferno-3/. In her commentary, Professor Barolini’s observes that “This space, the ground of transition, is not named by Dante; in the commentary tradition it is frequently called Ante-Hell or vestibule.” This is just one of a number of insights Professor Teodolinda provides in her comments on Canto 3.

- 4No way was Dante going to permit the neutrals to mar the symmetry of his masterwork, which he divides into the proportional realms of hell (the Inferno), purgatory, and heaven (Paradiso), each consisting of thirty-three cantos, a very particular number in deference to Jesus Christ, the savior’s, time on earth.

- 5“French Village of Mazan Torn Apart by Horror of Mass Rape Trial.” Accessed September 16, 2024. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cyvpd7zyprdo.

- 6This is an uncanny feature of the parable. Once you recognize the parable itself as a gift, watch out!

- 7Jean Dunbabin, “ROBERT GROSSETESTE AS TRANSLATOR, TRANSMITTER, AND COMMENTATOR: THE ‘NICOMACHEAN ETHICS,’” Traditio 28 (1972): 460–72.

- 8

- 9“Bible Gateway Passage: Matthew 22 – New International Version,” Bible Gateway, accessed October 5, 2024, https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Matthew%2022&version=NIV.

- 10https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/103-be-not-afraid-of-greatness-some-are-born-great-some

- 11“Lettera Apostolica Candor Lucis Aeternae Del Santo Padre Francesco Nel VII Centenario Della Morte Di Dante Alighieri.” Accessed October 11, 2024. https://press.vatican.va/content/salastampa/it/bollettino/pubblico/2021/03/25/0181/00393.html#ing.

Leave a Reply