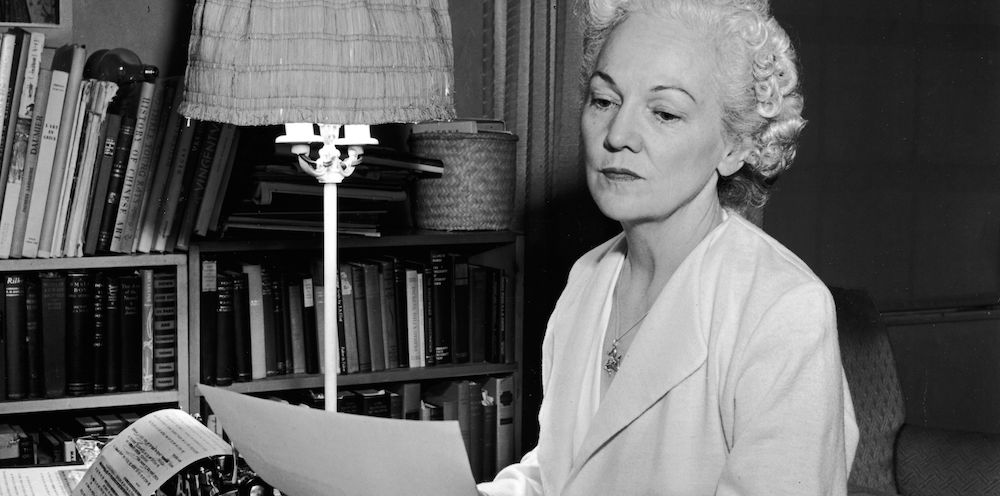

The story “He” is one peacock feather shy of a Flannery O’Connor story. Only it is a Katherine Anne Potter story and has its own luminance, not O’Connor’s sardonic delight in the grotesque.

Nonetheless, in her story, Porter puts in play more than a smattering of religious artifacts and allusions. She refers to the “simple-minded one” with upper-cased pronouns, in other words, not actually pronouns but nouns in the convention used to address deities or a supreme being.

In this story, He, if it isn’t referring to the simple-minded one, most naturally refers to Jesus Christ. He is sounded out the same as the pronoun—if only in one’s mind—but one cannot fail to notice that on paper it is visually distinct. It creates an aural / visual dissonance, which Porter begs us over and over again to consider and endure. We sound out “him” but we see “Him”.

The prominence of “neighbors” in this story is also extraordinary. Neighbors are a brooding presence from the beginning to the end. The word appears six times in the story, in the first paragraph, and in the last.

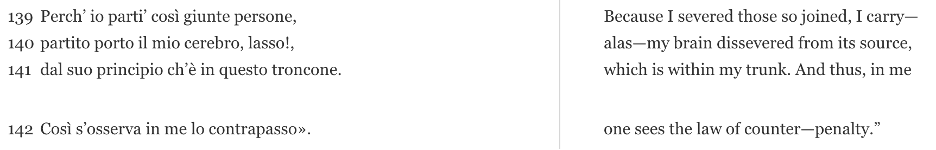

A “neighbor” is more than a prominent word in the New Testament. It is the word chosen by Christ to represent an “other” in the supreme rule of “to love one’s neighbor as one loves oneself”. Here supreme is meant in its utter literal sense. It is wildly significant in the context of the jumble of incongruous rules and laws and Good Housekeeping advice that make up the first five books of the Old Testament, the Pentateuch, when then and now we tend to accord the laws a common weight, relative merit notwithstanding.

How curious to love a neighbor when they seem (more on that later) as unlovable as the ones who appear in “He”, those who whisper behind the Whipples’s backs:

A Lord’s pure mercy if He should die.

It’s hard to imagine loving such a snarling brood as the Whipple’s neighbors. It puts a whole new spin on the task. It is closer to the paradoxical entreaty to “love one’s enemy”, which of course also comes from Him, now apparently the other “Him” in this story.

The innuendoes pile up. What now is the engagement between Him and Him? How do They relate?

At the very beginning, the story informs us:

Mrs. Whipple loved her second son, the simple-minded one, better than she loved the other two children put together. She was forever saying so.

We come to suspect that she is forever saying so because she is forever herself either unsure or incapable of this love she proclaims. We don’t know the nature of this love though we’re dropped a clue.

When Mrs. Whipple says to Mr. Whipple that “it’s natural for a mother to have feelings about Him,” the narrative invites the reader to think of unconditional love.

The simple-minded one, having few if any ways to reward his parents, in the form of report cards, witticisms, good looks, pleasing gestures, puts the unconditional love challenge to the test. Since such feelings are allegedly natural for a mother, how awkward for her when she doesn’t have them? And what if the neighbor’s find out!?

When we ask, what does Mrs. Whipple love about Him? The question starts to make more sense in its full ambiguity, i.e. as Him AND Him.

Now this is not the same as saying that Mrs. Whipple loves her second son. Mrs. Whipple is so utterly consumed by concern for what the neighbors think that we are forced to reckon with the other part of the dictum. Does Mrs. Whipple even love herself?

Porter has got love of self, love of others, and love of Him all knotted-up as if she planned it that way.

It also has a lot of “seeming” in it.

A plank blew off the chicken house and struck Him on the head and He never seemed to know it.

So in bad weather they gave her the extra blanket off His cot. He never seemed to mind the cold.

Porter wrings a lot out of this innocuous word. Most of the seeming comes from Mrs. Whipple. For her “seems” ties back to what others might think. She has no internal source of confirmation. Her whole idea of reality is tied up with how her neighbors might perceive things, perceive her. Hence, how things “seem”.

She has no perspective then on anything, most significantly on Him (the simple-minded one) or presumably Him (her savior).

With scant notice, Mrs. Whipple’s brother invites himself and his family over for a big Sunday dinner (he dares her to “put the big pot in the little one”). There is nothing to suggest that the brother is not every bit as poor as the Whipples or likely trolling for a good meal. Who better than a sibling to know your witnesses.

Mrs. Whipple, who is desperate not to look as poor as she desperately is, convinces her husband of the necessity to slaughter a pig for the meal over his objections.

“I’d hate for his wife to go back to say there wasn’t a thing in the house to eat,” she says.

The simple-minded one gets the job of snatching the pig from its mother sow’s teat and escaping “with the sow raging at His heels.”

Mrs. Whipple, who loves Him unconditionally, we’re supposed to believe, puts His life in mortal danger just to cover up for the “sin” of poverty.

The pickled peach in the roasted pig crackling in the middle of the table comes from Him. He (He) is the only one who scrambles among the branches of fhe family peach tree. He gets in trouble chasing a possum or hunting for eggs as if the second son understands fully the abysmal state of their larder. He gets it, it “seems”.

One suspects Mrs. Whipple doesn’t get the first thing about Him, her son. She makes a fuss out of serving Him first but is inwardly relieved that he keeps to Himself in the kitchen when He demurs and doesn’t join the rest of the family, his aunt, and uncle, and cousins in the dining room.

The meal is briefly a success. Later after company has parted, she frets that “her own brother will be saying around that we made Him eat in the kitchen!”

In a bleak winter, they borrow warm clothes from Him for His siblings who have to walk to school in the chill. For His outdoor chores, they arrange the loan of a coat from His father until he gets sick.

In the spring, after he’s recovered, they send him to fetch a bull from a neighbor for breeding, a modest attempt at better living through husbandry. The simple-minded one succeeds on his mission with perfect calm.

Whereas Mrs. Whipple sets him off on the mission with short-lived nonchalance. She goes from little caring to high-speed fretting in 3.9 seconds. Before He returns, she is in a self-inflicted lather that finally seems to expose her real concern: what people might say if He got hurt. It’s an incredible episode that is all whipped up in her head utterly divorced from the fact that the boy got back calmly without a murmur of incident.

As their fortunes sink lower, Mrs. Whipple fears “they’ll be calling us white trash next.” These “they” are a powerful lot. By coincidence, the “they” are a prominent concept in Heidegger’s philosophy, who likely would conclude that Mrs. Whipple is living “inauthentically”.

Their kids have seen enough. As soon as they can, they bolt from the farm.

Effectively, they’re getting away from their poor white trash parents. The irony is that the only discernable detail that makes them poor white trash parents is Mrs. Whipple’s state of mind.

The simple-minded son endures on the farm. Slips and falls on the ice. He has something like a stroke or a seizure. Appropriate healthcare: transferring Him expeditiously to a hospital by ambulance is frustrated and delayed. Instead, he goes in a “neighbors” ample wagon.

On a tortured ride to the hospital, the boy is crying in the cold. He is not seeming to cry, but crying. Her last thought in the story

Oh, what a mortal pity He was ever born.

This is extraordinary. The word “pity” bookends the story. In the beginning, Mrs. Whipple’s devout wish is not to be pitied by the “they”, the neighbors.

In the end, pity means a regrettable circumstance. It echoes what the neighbor’s supposedly said all along “a Lord’s pure mercy if He should die.”

At the very end, the reason the neighbor is “driving very fast, not daring to look behind him” is out of real pity. Mrs. Whipple’s love for Him was not what she claimed it to be. She did not love Him more than His two siblings put together. She did not love Him unconditionally, with “feelings more natural for a mother.”

Her condition, we profoundly suspect, accords equally to her simple-minded second son and her savoir. She is utterly cut-off, isolated, and impossibly tragic.

The neighbor cannot bear to bear witness.

Special thanks to George Saunders and fellow members of his Story Club for calling my attention to this story.