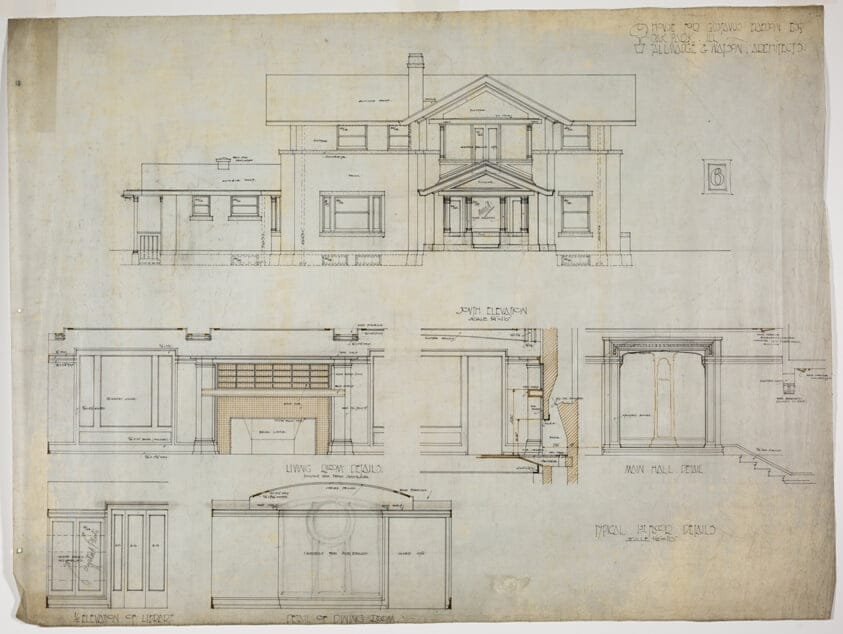

It was in the seventies. Bart Simpson was not yet a sparkle in Matt Groening’s creative eye. I was on a landing at the front of a large house, a landmark Prairie School architecture home in Oak Park, Illinois, restored by my parents, a few stair rungs below my mother who had come charging down the stairs from the second floor to engage me in an epic war of words.

I was seething with rage, pimples, and hormones, a product of age (I was a teenager) and disposition. Whatever we were arguing about is long since forgotten.

What I said in that instant, I will never forget. I said, “Mom, don’t have a cow.”

It was the wrong thing to say to a mother who grew up in the country, on farms. Carolyn erupted. I only remember anger and fury so intense it felt like I had swung a steel door open on its hinges to stick my head in a furnace. I’m not even sure she was forming sentences. The white heat of anger was all I felt.

Then, she calmed herself enough to explain the exact source of her anger. The mood was different. She was still seething but she wasn’t quite as much angry as she was appalled.

“Why, John,” she said, jaw tense, “if I had a cow, it would split my sides open.”

Which describes what happened next because, in about seven seconds, we were both doubled over in side-splitting laughter at the image of my mother birthing a cow, though, I suppose, in fairness to me, it would have more probably been a calf.

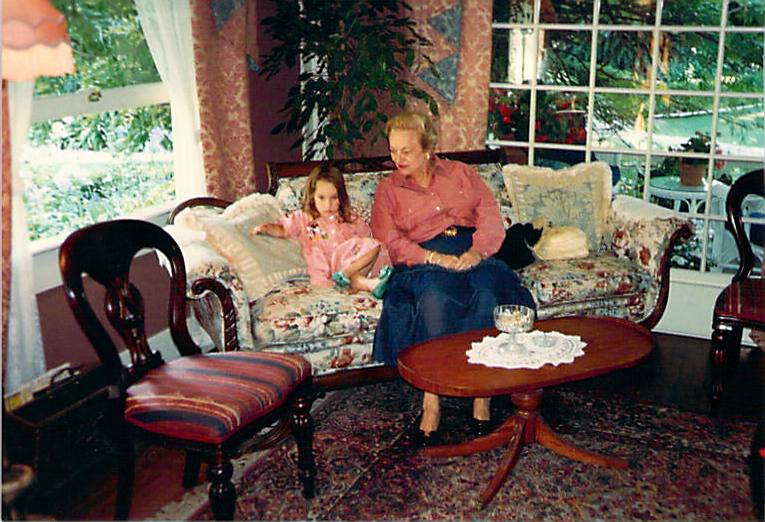

This was my introduction to the figurative mind of Carolyn Poplett, long before I had ever heard of Joseph Campbell and his demonstrations of the power of myth. This deeply figurative way of thinking was strange to me for most of my life.

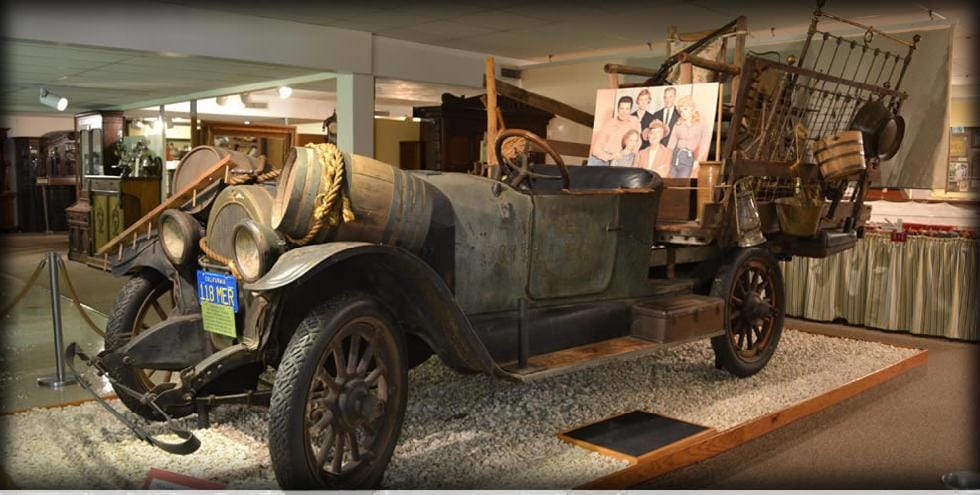

To a cocky Yankee lad, her hyperbolic flights of the imagination seemed like a deficiency of intellect, somehow tied to her Southern roots, as if my grandmother had weaned her from the breast with moonshine or she was a cousin of the Clampetts on The Beverly Hillbillies. Bless her heart.

But mom’s way of thinking is commonplace to me now: the paradox that you must take metaphor, figurative language, as literally as you dare. I do not know how to emphasize how strange it is to look back on how I used to think, before having adopted Carolyn’s wisdom. All I know is that the urgency of plumbing metaphor to its absolute depth now daily confronts me.

That’s not a bad frame of mind to work yourself into if you are a writer. But it is not a bad frame of mind to work yourself into if you wish to have a richly-rewarding, bountiful life no matter what you do.

A couple Sundays ago I had a misadventure that beat-up both of my feet to the point that I had to put myself in a wheelchair. The trigger was honorable enough. I received a call early in the AM from a caregiver. Unbeknownst to us, Carolyn was having a gout attack. Even with the caregiver’s help, she couldn’t rise to get dressed. I came over to help lift her. Stayed to lift her later in the evening to get her into bed. There were so many unusual circumstances piling up, I didn’t guess I would wake up the next day in agony. A few days later, I visited a foot doctor to learn that a pernicious wound had re-opened on my left foot—it took six months to close it the first time—and the right foot though not broken was at risk of collapsing from a condition known as Charcot’s foot. Both feet threatened to take me down long torturous paths[1] with iffy chances for full or partial recovery. There was a chance that I’d have to have surgeries on my right foot as I had done on my left. There was and remains the fear hovering in the air that, having already given up playing basketball, riding a bicycle might come next.

I was too emerging from a hypomanic episode, which, without correction, I suspect, can lead to bipolar disorder[2]. These are warnings to pull my life into order with maximum urgency. Yet, it is hilarious that the solution is to laze around and just be ridiculously kind to myself. How should that ever be a challenge? It is, but I am committed to reform.

If you take your metaphors seriously, the world starts to make sense in uncommon ways.

This was my frame of mind when I called mom two days ago. I couldn’t drive. I couldn’t go over to see her unless I took an Uber. I tried that once but there was too much banging around getting in and out of a car on the to and fro. I no longer wanted to risk any effect the journey might have on my recovery.

I called Carolyn instead. I didn’t know what to say to her. It occurred to me that we had never talked about religion. Not once. I do not recall seeing her upset or expressing her displeasure, when, as a boy, I was caught ditching Sunday school once out of the dozens of times when I didn’t get caught. Hey, I ditched bell ringing class too.

Carolyn’s dementia often seems so well advanced that it fools you. I determined, as I often do, to engage her intellect. If it’s philosophical or deep, anything about man’s place in the universe, it will snap her mind into focus.

On our phone call, I provided her with details of my physical and mental condition.

I omitted relating to Carolyn an incident, which ended on the last day of February in this, a leap year. On that night, was awakened by the sensation of a hand on the back of my neck before I decided to crawl across my apartment from bed to kitchen sink for a glass of water. As I traversed the tile in my kitchen on my knees, I started speaking to God and laughing. That sounds like madness, which is why I demurred from relating this story to Carolyn. Prosaically, speaking it is certainly easy to cobble together an explanation that a recent increase in my medications triggered it. I have every reason to believe that it was a catalyst. But I was laughing for the figurative significance of it. That God, providence, the universe, or whatever else you might want to call it had somehow arranged for me to be in this fix. I knew that the word human stemmed from a Hebrew word for “ground” or that it was related to the Latin word “humus”, which also means earth, ground, or soil, and is also related to the words “humiliation” and “humble”. There was no doubt in my mind—psychotropic drugs notwithstanding—that I had been brought down to this posture by the Supreme Being or a supreme force, again, take your pick, and so I was laughing with God as if to say “touché”. There was just no way in heck I was going to try to explain all that to my mother[3].

“You’ve really been through the mill,” she said. On cue, I thought about two millstones grinding grain into powder. “Not bad, mom,” I thought.

“Mom, have you ever noticed the difference between secular and religious speech? I’m starting to find religious speech much more expressive than secular speech. In a funny way, it’s more accurate. Doesn’t the expression “midlife crisis” sound bland, so bureaucratic that it makes you want to cringe?”

It was a softball question. Carolyn has the mind of a poet. She used to adore Emily Dickinson. I could sense her revulsion in the silence between words.

“So, mom, I like to think that I’m going through a rebirth. It’s the only way I can make sense out of what is happening to me.

“We’ve been to a lot of Christian weddings. Most of them that I remember had the ritual where the newlywed couple takes two candles symbolizing their former lives as single people so when they merge the two flames to light a third candle, it symbolizes the effect they hope to achieve by marriage.

“I always found that to be so charming, mom, but I must admit. I was charmed by it, I grasped it intellectually, but I didn’t really get it. I didn’t understand that marriage makes a couple symbolically a single item and that the symbolic unity runs way ahead of that ever coming to pass. I could never tell the difference between the starting gate and the finishing line. Marriage just makes it possible to become one and the goal of marriage is to make it so. It’s not given. You have to make it that way. And once you do, I believe, everything starts to make sense. Isn’t that how it was with you and dad?”

“Well, we had to work through a lot,” she said.

“So, in secular speech you have a “midlife crisis” but in religious speech you are “born again” with a lot of struggle along the way. Does that sound about right, mom? When I think about it, there is a gestation period, labor pains, the extreme life or death struggle of evicting the baby from the peaceful warmth of the womb. Only with a rebirth, there are contradictions. Who is the mother? Yourself? Of course, it is. It must be so, but how is that possible? You are no longer innocent as you were the first time. But isn’t the promise of rebirth, the promise to recover your innocence with the full benefit of keeping every scrap of knowledge you learned losing your innocence the first time?

“That’s what I think is going on with me, mom. Does that make sense?”

“Yes,” she said. And as I was explaining this to Carolyn, as I had rehearsed these thoughts with a friend a week or so earlier, it struck me anew that it was mom who had given me this sensitivity to metaphor, language, and a zeal for figurative intelligence.

Come to think of it, what could be more difficult in the undertaking than birthing oneself… unless it is “to have a cow”?

Originally posted March 30, 2022. Last revised April 1, 2022.

[1] We can decide later how easy it might be to follow both feet along two separate but equally torturous paths simultaneously.

[2] Hey! I’m paranoid too.

[3] For a fascinating description of truly profound religious experience, see the description of George Fox’s, the founder of the Quaker church, in William James’s The Variety of Religious Experience.

Leave a Reply